A woman’s voice is drifting across the space. High pitched, a cut glass accent. I’m not really listening. I’m looking at something in front of me. She might be talking about any trivial, upper class-concern. Then I hear words like urine, and honey, and dog shit, and I tune in. Someone asks a question: ‘What makes you anxious?’. A pause, the sound of traffic in the background. She answers. ‘My children, my work. Everything, really.’

It’s the voice of Charlotte Johnson Wahl, and I’m standing in the Museum of the Mind, looking at a picture she painted in 1974 while she was here, a patient at the Maudsley Hospital.

I read about her last year and was interested that she was Boris Johnson’s mother. A superficial reason, and I’m sure I’m not the first person to have the flippant and inappropriate thought that being his mum would make anyone a little crazy. I was intrigued enough to want to learn more about her.

The Museum of the Mind, opened in 2015 by Grayson Perry, is housed in an unremarkable 1930s building in South London, with neat rows of primulas flanking the entrance. This site, part of the South London and Maudsley NHS Trust, is the fourth home of the Royal Bethlem Hospital, first established in 1247 as a priory in Bishopsgate in the City of London. By 1403 it had six ‘insane’ patients and has cared for mentally ill patients ever since.

The main museum is fascinating, and I’ll write more about it soon. This time, I’m here to see an extraordinary collection of Charlotte’s work. The exhibition is called What It Felt Like, and the painting of the same name shows the artist bent over, cowed, trapped at the edge of the frame. Disembodied arms surround her, hands touching her, fingers pinched, while her hand is holding her hair.

Charlotte was a self-taught artist from the age of five. Before and after her hospitalisation, she painted portraits of famous friends and family. She painted throughout her eight month stay and when she left, the hospital staged an exhibition, where many pieces were sold. The curator of that exhibition, hospital archivist Patricia Allderidge, went on to found the Museum of the Mind. Now, half a century later, the Museum has staged this retrospective, bringing her work to new audiences.

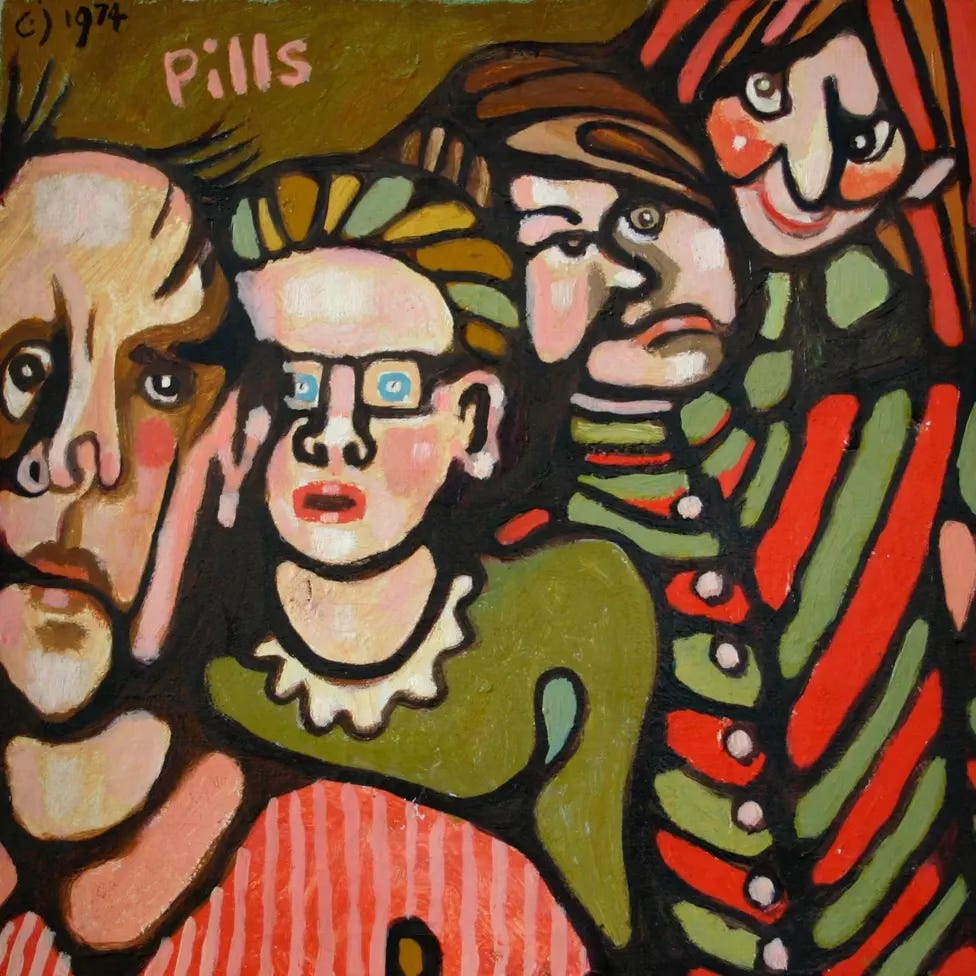

The style is almost pop art, bursting with a 1970’s colour palette. She said that her Maudsley style was very distinctive and that later she could instantly recognise if she painted a picture there. The vibrancy is a counterpoint to the pain and distress she is conveying.

The words that I hear on entering the gallery come from an interview with Charlotte in 2015, when she was in a car on her way to visit the Maudsley.

Her experience at the hospital was a long way from the positive messaging about modern day treatment in the rest of the Museum. It’s brave and honest of the Maudsley to be prepared to highlight it. This is not a tale of therapeutic kindness.

A self-portrait shows her hunched, ears tucked into her shoulders, eyes closed, mouth turned downward in defeat, arms clutching her chest, her knuckles white. Hands are a repeated motif throughout her work. She was diagnosed with ‘obsessive-compulsive neurosis’, which we would probably now call OCD. She had a phobia about dirt and would obsessively wash her hands to the point that they bled.

In the interview, Charlotte describes her treatment as ‘repressive’ and adds that ‘even normal people’ would object to it. The consultants, who she called The Firm, recommended ‘exposure and response prevention’ therapy. She was forced to endure the very things she feared. They would put dog faeces on her shoe and make her walk around with it all day. They dabbed honey, or urine, on her hands and sent her off for the morning to paint. She was prevented from washing her body, or her hands, regularly. Patricia Allderidge later described it as ‘patient abuse’.

Ask And Get No Reassurance shows multiple hands growing out of her hands, which are covered in droplets which could be the urine or honey she talked about. A third hand, presumably of a doctor or nurse, is beckoning her. At one point she was made to move to a different room to paint, which caused her horror. Phobia 1 was her response, showing her body covered in insects.

Charlotte also had to attend group therapy sessions, which she hated, fearing that ‘anyone might probe and attack’ the tenderest parts of her consciousness. In Morning Group there is sense of enforced intimacy - the group pressing in on the viewer, limbs crushed together, crowding the frame.

Her work rate was incredible. She produced 80 paintings while she was here - more than two a week. She wasn’t the first artist at the Maudsley to paint during her stay, but this goes way beyond the practice of art as therapy. This is art as compulsion. I have a sense that the work grounded Charlotte and allowed her to exert some element of control in the midst of personal turmoil and brutal treatment.

Charlotte couldn’t bear to sit at a table if it had crumbs on it, so in her painting Canteen With No Food she simply takes the food out of the picture entirely. It depicts patients crowding round, hands and arms reaching across empty tables. The writer Jilly Cooper bought this at the first exhibition.

There is pain and distress in the work, but also a strong streak of humour and defiance, which I love. Phobia 1 and other paintings show her thumbing her nose at the staff in a powerful ‘Fuck You’ artistic gesture.

Her gift to the hospital when she left was called It Hasn’t Worked, which now hangs in the permanent exhibition. How’s that for a review of her stay?

The most poignant work in the exhibition relates to Charlotte’s family. She was in her early 30s when she was at the Maudsley, with four children aged between two and nine years old. She had followed her husband Stanley Johnson to Washington, New York and back to England and while she was hospitalised the family moved to Brussels, so visits were rare and clearly very emotional. These paintings show a mother and a family in turmoil – sad, broken, disjointed. In Johnson Family Hanged by Circumstance, children with blond mops of hair hang from a washing line. Charlotte herself looks upward in anguish. Don’t Be Sad shows her crying, reaching out an arm to one child while others stand downcast or tumble on the floor. A figure who is clearly Stanley Johnson, looks away, sideways, at the viewer.

One of the most striking portraits is of her husband, titled Stanley Towards The End. We don’t know what end she is referring to – her stay or their relationship. Standing in front of it, I see a cold-eyed dandy, his outfit perfectly toned, the suit with the wide lapels of the time, a smart wristwatch visible above his cuff. The wording Bruxelles is visible in the corner of the painting. The impassivity in his face tells me that he is a subject here, not a partner.

The most evocative painting for me is Shake Her Down, Talk to Her…Oh, Just Leave Her! The title alone tells a story of fear and frustration. Charlotte is at the top of a tree in autumn, once again trying to exit the scene. In the opposite corner her children at the bottom of the tree, stretching to reach her. Elsewhere adults, one with a bag, perhaps family or clinicians, walk away.

As she made clear in her gift to the Maudsley, the treatment didn’t work. Once discharged, she went back to Brussels and had private treatment which eventually helped her to deal with her phobias. She was asked in the 2015 interview whether she felt stigmatised for being mentally ill, and she replied, ‘yes, terribly. In those days it wasn’t in the least bit talked about.’ However she was immensely courageous in exhibiting her work after her discharge, because it was the first time that the Maudsley had held an exhibition by a named patient.

Charlotte went back to her family, and Stanley, until they divorced in 1979. Around three years later she was diagnosed with Parkinson’s, yet she carried on painting throughout the rest of her life and went on to marry historian Nick Wahl and live in New York. She died in 2021 aged 79.

Before I leave, I watch the short film again. It’s no longer a disembodied voice. It belongs to someone who has allowed me to step inside a fragment of her life, share her fears and be inspired by her talent, resilience and humour. I wonder why she was returning to the Maudsley in 2015. Perhaps it was for the opening of the Museum.

The final part of the film shows the car pulling up outside. You can see from the expression on her face that, 40 years later, this was still a place that terrified her.

The film ends there. The final frame tells us that she decided not to go in.

Carol

I’ll come back to the rest of the Museum of the Mind in my next post. I’d love to know what you think of Charlotte’s work, so please comment below.

The exhibition is on until 29 March 2025 and is open to the public Wed – Sat. The bookshop also stocks the catalogue.

You can check out more of her work here

Although not my sort of art, I can now appreciate the paintings, and, having heard your calm explanation of her awful predicament, I can look at them anew.

None of us are our mothers, but our perception of the world is always first and foremost, through their eyes. Thank you for reminding me of this.